“Might part of the solution be hiding in the unwanted plants, the bitter, weedy roots and greens that intrude on our fields and gain footholds in waste places?” ~Guido Masé, The Wild Medicine Solution

“Among the most pervasive flavors found in healing herbs is that of bitterness. Isn’t it interesting that this flavor, so wide-spread and variant in so many of our most trusted remedies, is an unfamiliar one to us? One that people often claim deters them from plant medicines? If plants’ tongues speak to our tongues, then what do we not hear when we taste no bitterness?” ~jim mcdonald

“Among the most pervasive flavors found in healing herbs is that of bitterness. Isn’t it interesting that this flavor, so wide-spread and variant in so many of our most trusted remedies, is an unfamiliar one to us? One that people often claim deters them from plant medicines? If plants’ tongues speak to our tongues, then what do we not hear when we taste no bitterness?” ~jim mcdonald

I attended the International Herb Symposium last summer. Held on the beautiful grounds of Wheaton College in Norton, Massachusetts, this biannual gathering brings together herbalists and herb enthusiasts from around the world. I spent three jam-packed days going from one class to the next, heading out on plant walks, visiting the vendors centre and enjoying the evening activities of storytelling and rousing keynote addresses and speeches.

I’d be hard pressed to pick a favourite class or activity, they were all so rich and informative, but a real highlight of the symposium that led to a major shift in my herbal thinking, was Guido Masé’s class on herbal bitters.

I had long known of the importance of bitters in the diet and went through sporadic bursts of taking them before meals from time to time, but it was Guido’s class that fully elucidated the essential significance of bitters and why we should all be incorporating them regularly into our daily lives.

Humans are able to detect five basic tastes: sweet, sour, salt, umami and bitter. Of all the tastes, we are most sensitive to bitter, able to detect it a very low thresholds. Historically, this sensitivity would have been a protective measure for hunter-gatherer peoples eating wild foods, some of which were toxic. Many of the toxic chemicals in plants have a bitter taste, thus providing a warning signal from nature to be aware of what is being ingested. Over time however, as we coevolved with plants, we developed a fascinating and complex relationship with bitter tastes and the plants that contain them.

We developed a highly specialised family of taste receptors called T2Rs, able to recognise a broad range of bitter compounds including iridoids, alkaloids, lactones, flavonoids and saponins. These receptors are found on the tongue, in the throat, the GI tract and surprisingly in the pancreatic duct, the liver, gallbladder, small intestine and even in the lungs and brain cells!

Some pretty amazing things start to happen when those receptors are stimulated by a bitter tasting substance. In his book, The Wild Medicine Solution: Healing with Aromatic, Bitter, and Tonic Plants, Guido Masé writes, “Stimulating T2Rs has profound implications throughout the digestive system and in the liver…getting the signal of bitterness on the tongue increases antioxidant enzyme and bile secretion in the liver through the combined action of hormones…and nerves, such as the vagus nerve.”

In his class at the Symposium, Guido spoke more about the pharmacology of T2R stimulation. He posits that bitterness provides a necessary challenge or stress to the GI tract that alerts the digestive system to come online and be prepared for action. This challenge also awakens chemical processing pathways in the liver. Once a bitter taste is detected on the tongue, a chemical signal is sent to the vagus nerve which sets off a chain reaction of events; salivation increases, the esophagus relaxes, the hormone gastrin is secreted which regulates the production of gastric acid, production of the enzyme pepsin increases, pancreatic enzymes and bile are released, peristalsis is initiated and digestive juices are secreted in the small intestines.

The effects of all these actions are as profound as they are wide-reaching. When stimulated by the bitter taste, the entire digestive tract functions more effectively and efficiently. Food stays in the stomach longer, allowing it to be better broken down before passing into the intestines, nutrients are better absorbed and assimilated by the body, sugar is released into the bloodstream more slowly, appetite is regulated and the metabolic and detoxification processes of the liver are aided. All this in turn leads to less heartburn, gas, bloating, diarrhea and constipation, lower rates of obesity, better blood sugar control, reduced inflammation, less allergic sensitivity and increased overall health and vitality.

In fact, as Masé suggests, it is the absence of bitters, perhaps more so than the excess of sugar, fat and salt, in our diet that may be in large part responsible for many of the chronic diseases we see in Western culture today. Obesity, diabetes, autoimmune disorders, the suite of digestive conditions and diseases such as IBS, Crohn’s, colitis and intestinal permeability (leaky gut) may all see dramatic improvement by adding bitters into the diet.

I’d be hard pressed to pick a favourite class or activity, they were all so rich and informative, but a real highlight of the symposium that led to a major shift in my herbal thinking, was Guido Masé’s class on herbal bitters.

I had long known of the importance of bitters in the diet and went through sporadic bursts of taking them before meals from time to time, but it was Guido’s class that fully elucidated the essential significance of bitters and why we should all be incorporating them regularly into our daily lives.

Humans are able to detect five basic tastes: sweet, sour, salt, umami and bitter. Of all the tastes, we are most sensitive to bitter, able to detect it a very low thresholds. Historically, this sensitivity would have been a protective measure for hunter-gatherer peoples eating wild foods, some of which were toxic. Many of the toxic chemicals in plants have a bitter taste, thus providing a warning signal from nature to be aware of what is being ingested. Over time however, as we coevolved with plants, we developed a fascinating and complex relationship with bitter tastes and the plants that contain them.

We developed a highly specialised family of taste receptors called T2Rs, able to recognise a broad range of bitter compounds including iridoids, alkaloids, lactones, flavonoids and saponins. These receptors are found on the tongue, in the throat, the GI tract and surprisingly in the pancreatic duct, the liver, gallbladder, small intestine and even in the lungs and brain cells!

Some pretty amazing things start to happen when those receptors are stimulated by a bitter tasting substance. In his book, The Wild Medicine Solution: Healing with Aromatic, Bitter, and Tonic Plants, Guido Masé writes, “Stimulating T2Rs has profound implications throughout the digestive system and in the liver…getting the signal of bitterness on the tongue increases antioxidant enzyme and bile secretion in the liver through the combined action of hormones…and nerves, such as the vagus nerve.”

In his class at the Symposium, Guido spoke more about the pharmacology of T2R stimulation. He posits that bitterness provides a necessary challenge or stress to the GI tract that alerts the digestive system to come online and be prepared for action. This challenge also awakens chemical processing pathways in the liver. Once a bitter taste is detected on the tongue, a chemical signal is sent to the vagus nerve which sets off a chain reaction of events; salivation increases, the esophagus relaxes, the hormone gastrin is secreted which regulates the production of gastric acid, production of the enzyme pepsin increases, pancreatic enzymes and bile are released, peristalsis is initiated and digestive juices are secreted in the small intestines.

The effects of all these actions are as profound as they are wide-reaching. When stimulated by the bitter taste, the entire digestive tract functions more effectively and efficiently. Food stays in the stomach longer, allowing it to be better broken down before passing into the intestines, nutrients are better absorbed and assimilated by the body, sugar is released into the bloodstream more slowly, appetite is regulated and the metabolic and detoxification processes of the liver are aided. All this in turn leads to less heartburn, gas, bloating, diarrhea and constipation, lower rates of obesity, better blood sugar control, reduced inflammation, less allergic sensitivity and increased overall health and vitality.

In fact, as Masé suggests, it is the absence of bitters, perhaps more so than the excess of sugar, fat and salt, in our diet that may be in large part responsible for many of the chronic diseases we see in Western culture today. Obesity, diabetes, autoimmune disorders, the suite of digestive conditions and diseases such as IBS, Crohn’s, colitis and intestinal permeability (leaky gut) may all see dramatic improvement by adding bitters into the diet.

“It is a common saying in the natural health arena that all disease begins in the gut. It is undeniable that our guts have wide implications on our health. If we are unable to digest, assimilate and expel elements from the food we ingest then a wide range of dysfunctions can occur, including digestive upsets to immune system imbalance.” ~Rosalee de la Foret, Bitter Herbal Medicine

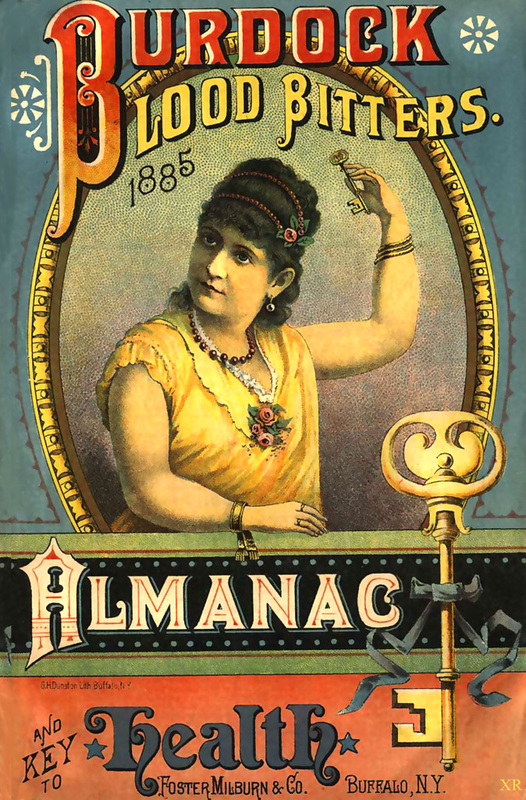

There is actually a long tradition of taking bitters for improved digestion in many cultures around the world. Bitter greens, most often in the form of wild, local weeds, have a long history of use among many cultures. A small salad that includes bitter greens is still very common in French cuisine. Europeans in general still maintain the practice of consuming bitter herbs. In Germany, herbalist Christopher Hobbs has estimated that across the nation, 20 million doses of bitters are taken every day. In Greece the traditional dish horta is eaten daily. It is a mix of chicory and dandelion greens cooked and drizzled with plenty of olive oil. A similar dish, hindbeh’atteh, is prepared in Lebanon with dandelion, garlic, lemon juice and olive oil. Bitter, pickled vegetables are frequently eaten in the Middle East. Drinking herbal bitters as a digestif or aperitif was quite popular in America in the late 1800’s and early 1900’s and still is in many European countries. Campari, Angostura and Chartreuse are just a few examples of alcoholic bitters and ones that are readily available in most liquor stores and even some grocery stores. These would be sipped in small amounts before or after a meal to aid digestion.

There is actually a long tradition of taking bitters for improved digestion in many cultures around the world. Bitter greens, most often in the form of wild, local weeds, have a long history of use among many cultures. A small salad that includes bitter greens is still very common in French cuisine. Europeans in general still maintain the practice of consuming bitter herbs. In Germany, herbalist Christopher Hobbs has estimated that across the nation, 20 million doses of bitters are taken every day. In Greece the traditional dish horta is eaten daily. It is a mix of chicory and dandelion greens cooked and drizzled with plenty of olive oil. A similar dish, hindbeh’atteh, is prepared in Lebanon with dandelion, garlic, lemon juice and olive oil. Bitter, pickled vegetables are frequently eaten in the Middle East. Drinking herbal bitters as a digestif or aperitif was quite popular in America in the late 1800’s and early 1900’s and still is in many European countries. Campari, Angostura and Chartreuse are just a few examples of alcoholic bitters and ones that are readily available in most liquor stores and even some grocery stores. These would be sipped in small amounts before or after a meal to aid digestion.

“At the core, the age-old bitter food traditions remain the bedrock of dietary wisdom promoting general digestive health accessible to everyone, often in the form of wildly abundant roots and weeds.” ~Steve Byers, A New Taste for Bitters

Unfortunately, this practice has been all but lost in North America. In fact, the bitter flavor itself has virtually disappeared from our cuisines and rarely do we taste bitter on our palates. When we do, we shudder and grimace with revulsion and do our best to avoid another bitter experience in the future.

This is understandable. Our aversion to bitterness is an evolutionary response designed to protect us from eating poisonous plants. However, over time humans adapted and eventually became able to consume formerly toxic plants by developing ways of processing the harmful chemicals and rendering them inert, mostly by way of the liver and digestive tract. This relationship between humans and bitter plants evolved to the point where the bitterness is now exceptionally beneficial, and some like Guido Masé would say, even essential to digestive and overall health. He writes, “bitter plants, long sources of potential toxins, may at this point be so entwined in our metabolic machinery that we cannot live without them.”

“It is my opinion that the nearly complete lack of bitter flavoured foods in the overall U.S. and Canadian diet is a major contributing factor to common cultural health imbalances…” ~James Green

Yet, when given the choice, modern North Americans tend to almost exclusively opt for carb-heavy food that tastes sweet, salty, rich and unctuous. We are now seeing the effects of these taste preferences in the rising rates of obesity, diabetes, declining cardiovascular health, chronic disease and serious digestive illness. Again, one has to wonder, how much of this is due to excess consumption of salt, sugar and fat and how much is in part due to the lack of bitters in the diet?

Masé makes a compelling case for the latter argument:

“While we blame so much of our modern public health concerns on the rise of sweet in the Western diet, we can’t forget that at the same time we handily eliminated much of what was bitter and wild in our food…We have removed the bitter flavor from our diets, both by reducing the amount of wild, weedy foods we consume and be refining and overdosing on starchy staples…The consequences have been a series of imbalances in the human physiology: digestion has become sluggish and ineffective…and blood sugar levels have begun to seesaw in dangerous ways…”

The good news is that it is very easy to find our balance again. Simply by adding bitters back into the diet on a regular basis, we can begin correcting the damage and regain what we have lost. If we can accustom our palates once more to appreciate bitter flavours, we will very quickly feel the beneficial effects that this miraculous taste sensation can stimulate in our system.

It can start with a trip to the grocery store and adding a few key items to our grocery list. Kale is considered a mild tasting bitter and given all of its other health benefits, this seems an obvious choice and a good place to start. In the lettuce section pick up some of the different types of chicory like frisée, radicchio, endive or escarole and add them in increasing amounts to your salads. Many grocery stores now accommodate the cuisines of other cultures and dandelion is becoming easier to find on the produce shelves. Better yet, why not step out into your backyard and gather the dandelion greens growing there? If you need to temper the bitter, plants growing in the shade, in the early spring or the late fall after a couple of frosts will be milder.

Take up the habit of indulging in a bitter aperitif or digestif with your meals and slowly savour a bitter cocktail with friends and family. There is a growing trend of serving bitters in bars these days and bartenders are putting bitters back on the menu.

Many herb companies formulate their own herbal bitter combinations and these tinctures can be easily found in most health food stores. The blends will include some of the classically bitter herbs such as dandelion (Taraxacum officinale), burdock (Arctium lappa), yellow dock (Rumex crispus), gentian (Gentiana spp.), artichoke (Cynara scolymus), and wormwood (Artemisia absinthum) among others. They are almost always mixed with aromatic, carminative herbs like ginger and sometimes something a little sweet such as licorice.

In his class, Guido gave a few guidelines on when to take bitters. For those that suffer from upper GI symptoms he recommends taking bitters after meals, and for lower GI symptoms, before meals. For those that have had their gall bladder removed he recommends taking bitters 15 to 20 minutes before a meal, and cautions that bitters are contraindicated with blocked gall bladder ducts. Taking bitters between meals can help stabilize blood sugar levels.

Energetically, bitters tend to be cooling and drying and may exacerbate an already cold and dry constitution. In this case it would be important to balance a bitter formula with warming herbs such as fenugreek, juniper berries, ginger or angelica.

Aside from constitutional, energetic considerations, bitters, when taking in small amounts, on a regular basis are very safe and well-tolerated by most everyone. They are an important and even necessary element of good digestive health and proper liver function. Consuming bitter herbs reaches back into pre-history and until modern times, their use has come down through the ages in a deeply entwined and intimate relationship with humans. Now, as this relationship is being threatened by other more tempting tastes, we need to reexamine our taste preferences and balance our desires and cravings for salt, sweet and fat and embrace a little bit of bitter in our lives. It might just be the simplest change you can make with the most profound effects on digestive health and wellbeing. And to that I will raise a glass of bitter tonic!

Resources:

The Wild Medicine Solution: Healing with Aromatic, Bitter and Tonic Plants, Guido Masé

Bitters, presented by Guido Masé, 11th International Herb Symposium Proceedings

Bitter Herbal Medicine e-book, Rosalee de la Foret

A New Taste for Bitters, Journal of the American Herbalists Guild, Volume 10 I Number 2, Steve Byer

Blessed Bitters, jim mcdonald

Image sources:

http://www.flickr.com/photos/boston_public_library/8558178038/, http://www.flickr.com/photos/x-ray_delta_one/10898238654/

Unfortunately, this practice has been all but lost in North America. In fact, the bitter flavor itself has virtually disappeared from our cuisines and rarely do we taste bitter on our palates. When we do, we shudder and grimace with revulsion and do our best to avoid another bitter experience in the future.

This is understandable. Our aversion to bitterness is an evolutionary response designed to protect us from eating poisonous plants. However, over time humans adapted and eventually became able to consume formerly toxic plants by developing ways of processing the harmful chemicals and rendering them inert, mostly by way of the liver and digestive tract. This relationship between humans and bitter plants evolved to the point where the bitterness is now exceptionally beneficial, and some like Guido Masé would say, even essential to digestive and overall health. He writes, “bitter plants, long sources of potential toxins, may at this point be so entwined in our metabolic machinery that we cannot live without them.”

“It is my opinion that the nearly complete lack of bitter flavoured foods in the overall U.S. and Canadian diet is a major contributing factor to common cultural health imbalances…” ~James Green

Yet, when given the choice, modern North Americans tend to almost exclusively opt for carb-heavy food that tastes sweet, salty, rich and unctuous. We are now seeing the effects of these taste preferences in the rising rates of obesity, diabetes, declining cardiovascular health, chronic disease and serious digestive illness. Again, one has to wonder, how much of this is due to excess consumption of salt, sugar and fat and how much is in part due to the lack of bitters in the diet?

Masé makes a compelling case for the latter argument:

“While we blame so much of our modern public health concerns on the rise of sweet in the Western diet, we can’t forget that at the same time we handily eliminated much of what was bitter and wild in our food…We have removed the bitter flavor from our diets, both by reducing the amount of wild, weedy foods we consume and be refining and overdosing on starchy staples…The consequences have been a series of imbalances in the human physiology: digestion has become sluggish and ineffective…and blood sugar levels have begun to seesaw in dangerous ways…”

The good news is that it is very easy to find our balance again. Simply by adding bitters back into the diet on a regular basis, we can begin correcting the damage and regain what we have lost. If we can accustom our palates once more to appreciate bitter flavours, we will very quickly feel the beneficial effects that this miraculous taste sensation can stimulate in our system.

It can start with a trip to the grocery store and adding a few key items to our grocery list. Kale is considered a mild tasting bitter and given all of its other health benefits, this seems an obvious choice and a good place to start. In the lettuce section pick up some of the different types of chicory like frisée, radicchio, endive or escarole and add them in increasing amounts to your salads. Many grocery stores now accommodate the cuisines of other cultures and dandelion is becoming easier to find on the produce shelves. Better yet, why not step out into your backyard and gather the dandelion greens growing there? If you need to temper the bitter, plants growing in the shade, in the early spring or the late fall after a couple of frosts will be milder.

Take up the habit of indulging in a bitter aperitif or digestif with your meals and slowly savour a bitter cocktail with friends and family. There is a growing trend of serving bitters in bars these days and bartenders are putting bitters back on the menu.

Many herb companies formulate their own herbal bitter combinations and these tinctures can be easily found in most health food stores. The blends will include some of the classically bitter herbs such as dandelion (Taraxacum officinale), burdock (Arctium lappa), yellow dock (Rumex crispus), gentian (Gentiana spp.), artichoke (Cynara scolymus), and wormwood (Artemisia absinthum) among others. They are almost always mixed with aromatic, carminative herbs like ginger and sometimes something a little sweet such as licorice.

In his class, Guido gave a few guidelines on when to take bitters. For those that suffer from upper GI symptoms he recommends taking bitters after meals, and for lower GI symptoms, before meals. For those that have had their gall bladder removed he recommends taking bitters 15 to 20 minutes before a meal, and cautions that bitters are contraindicated with blocked gall bladder ducts. Taking bitters between meals can help stabilize blood sugar levels.

Energetically, bitters tend to be cooling and drying and may exacerbate an already cold and dry constitution. In this case it would be important to balance a bitter formula with warming herbs such as fenugreek, juniper berries, ginger or angelica.

Aside from constitutional, energetic considerations, bitters, when taking in small amounts, on a regular basis are very safe and well-tolerated by most everyone. They are an important and even necessary element of good digestive health and proper liver function. Consuming bitter herbs reaches back into pre-history and until modern times, their use has come down through the ages in a deeply entwined and intimate relationship with humans. Now, as this relationship is being threatened by other more tempting tastes, we need to reexamine our taste preferences and balance our desires and cravings for salt, sweet and fat and embrace a little bit of bitter in our lives. It might just be the simplest change you can make with the most profound effects on digestive health and wellbeing. And to that I will raise a glass of bitter tonic!

Resources:

The Wild Medicine Solution: Healing with Aromatic, Bitter and Tonic Plants, Guido Masé

Bitters, presented by Guido Masé, 11th International Herb Symposium Proceedings

Bitter Herbal Medicine e-book, Rosalee de la Foret

A New Taste for Bitters, Journal of the American Herbalists Guild, Volume 10 I Number 2, Steve Byer

Blessed Bitters, jim mcdonald

Image sources:

http://www.flickr.com/photos/boston_public_library/8558178038/, http://www.flickr.com/photos/x-ray_delta_one/10898238654/

RSS Feed

RSS Feed